Egner & Koutroulis

The name “Cass Corridor” makes reference to a historical landmark and cultural arts movement in the City Detroit. Its legacy speaks to the psychological, socioeconomic, artistic currents, and the climate of the world in the 1960’s and ‘70s. This time period was one of emergence from old traditions. A time of questioning one’s self and the power structures that were in place. It was a time of international struggle. War, political trauma, and the day-to-day fear of the unknown affected people worldwide. Looking back at this time in America, and in Detroit, it is evident how the times were changing the political and social landscape. In such turbulent times, which fueled heated debates about war and civil rights, the blatant tension that simmered were hard to ignore.

The saying “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure” rings true in terms of the Cass Corridor. Originally the Corridor was the home to upper middle class families, but as the auto industry in Detroit declined in the 1960’s, the demographic changed. The new residents consisted mostly of students and people struggling at or below the poverty line. The Cass Corridor’s reputation was seen as a place for a darker side of life, being full of “loose people” referring to alcoholics, dope addicts, pimps and prostitutes, artists, bag ladies, and misfits. Yet those who considered the neighborhood filled with the “scum of the earth” were contrasted by those who saw it as a haven, as their place. The 1967 Uprising in Detroit, which lasted 5 days and was considered one of the most destructive acts of racial violence in U.S. history, created chaos, violence and instability in the region. It was an event that caused generational trauma and destruction to the city’s infrastructure. These scars to the community are still present in the city, and surrounding suburbs, today. While the fallout of the destruction catapulted a white flight (white families moving to the suburbs), many artists flowed into the city taking advantage of inexpensive rent and expanded freedom of living in an environment with less systemized regulations than other parts of the city. These were revolutionary times, in and out of the art world. In the face of all that was happening in the city, people witnessed many endings and beginnings that coexisted. The boundaries between life and death were frequently at the forefront of thought, and consequently motivated people to push tradition and their own personal thresholds by experimentation of all kinds: drugs, sex, music, and art.

One of the major facets of the growth that the Cass Corridor movement produced was the culture shift within the Art Department at Wayne State University (WSU), which was located in the heart of the Corridor. This transformation within the school changed the approach of how art was taught. Its impact was felt in the community by the influential instructors who taught there and the wave of graduating students. The shift in the department was from a very traditional to a more modernist approach to teaching. There were two new faculty members that were appointed in 1966, painter John Egner and printmaker Aris Koutroulis. These two individuals became the cornerstones of the art department. Their influence on the Cass Corridor art scene was through their art work, and through the way they nurtured their students.

Endlessly fascinating, Egner and Koutroulis reflected the intricacies of the environment around them. Koutroulis, a printmaker born in Piraeus, Greece, came to WSU after completing graduate school at Cranbrook Academy of Art. Egner, a painter from Philadelphia, earned a Masters of Fine Arts degree from Yale University prior to his arrive to Wayne. Their work and lifestyle was prolific and adaptive in the tumultuous decades of their development. Not only were they renowned for their teaching within the university, but they were also known for their stories, for their complexity as people and as mentors. The combination of all of these elements created a perfect storm which blazed a path for young artists in the Corridor to experiment and explore their passions. The influence of this time can still be felt in the WSU Art Department today.

In the Detroit art community, one still hears Egner’s name. His down-to-earth, thoughtful personality was translated through his teaching style. He omitted certain traditions set before him, instead of assigning lists of specific paints and materials to buy, and he told his students to “buy the paints that feel right to you” and “to work on surfaces that fit your practice”. Instead of teaching his students traditional painting techniques, or teaching students the way he paints, he had them explore and discover what really worked for them personally. He was as much a mentor as he was an instructor. He helped young artists learn to observe their inner voices, and motivations, and nurtured them.

Gilda Snowden, WSU painting alum, spoke of John Egner as a mentor, in her Kresge Artist Award video , “My mentor told me once, when we went to the museum, to the DIA and there was this room, and this gallery was in their foray into showing African American Art and the history of African American Arts, and it was this little tiny room. So, I was there and I was a little militant back in those days. I was always wearing a captain’s coat from Korea that I got from an Army/Navy place. I said ‘Is this all I have to look forward to, this little room?’ Even though it was the DIA, this little room? ‘This is it?’ I asked, and he said, ‘The one thing you have to remember is that no one can stop you from making your work in your studio.’ and when he said that, I was like ‘yeah, no one’s going to stop me’ and years go by and I end up with my work being exhibited on permanent display not far from that room, but in a much larger context.”

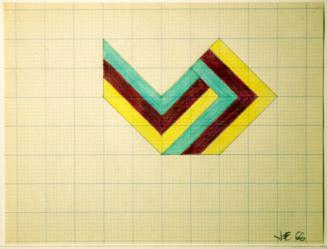

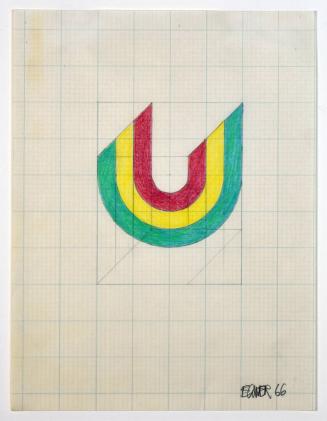

John Egner found his style through a process he compared to Mark Rothko and his mentor at Yale, Jack Tworkov. Rothko never felt he was artistically talented or thought that he could draw realistically, but he always knew he was a good designer. Believing that “[to truly make art] you can’t do what you can do [or what comes easy to you], and you can’t do what you [truly] can’t do”. Rothko naturally fell into a space in-between his natural talents and his flaws, which is where his art was made. Egner went through a similar process; he did not consider himself an impressive draftsman but had a strong sense with geometrical design influenced by his father, who worked in advertising.

Aris Koutroulis was equally influential to his students. He’s cited Paul Dufour, an artist who attended Yale (just like Tworkov and Egner), and Caroline Durieux for contributing to his evolution as a young artist. Koutroulis felt Durieux “was just absolutely amazing in her way of life and her way of thinking, the clarity of her mind and her presence of knowing what is and what isn’t; [looking at] what’s real and what is illusionistic.”

Growing up during World War II, in Greece, Koutroulis experienced a tumultuous childhood. In Koutroulis’ oral history with the Smithsonian, he spoke about living through many bombings and coming close to death as a child due to starvation. For Koutroulis, the trauma of his childhood stayed with him as he forged a life as a U.S. citizen and as an artist in Detroit. During his time at WSU, he was a cornerstone of the Printmaking Department. He was very beloved by students because of his kind, gentle manner partnered with his ambition as an artist. His ambitious side allowed him to teach in a way that challenged his student’s ideas of what art was, as well as their own personal art making processes. His empathetic side came from growing up with the realities of war, and then later as a soldier in the U.S. Army. His empathy came through experience; when talking about earning a Masters of Fine Arts in Printmaking, “I had a nervous breakdown... A long time ago when I was at Cranbrook all this stuff came out. I mean it was just an incredible amount of catharsis of dying actually and being reborn again somehow. It was incredible. It lasted a long time.” Aris understood what it took to transcend his own trauma through art making, which helped him to be resilient as an artist and as a man.

Koutroulis’s art was a cathartic way of processing everyday life, as well as a deep personal and formal exploration. Koutroulis expressed, “What really intrigues me about the line is that it doesn’t exist in nature. It is total a manmade thing; whereas everything else – texture, color, form, space – all those elements in the arts do exist in some way… but a line doesn’t exist… so it was a very profound thing for me to use as a vehicle for artistic images – and not just the line itself. I mean the various qualities of what a line can do.” Adding an analysis of his work, “There was an aura about it, a magic about it that they called talent. I’m not even sure if there is such a thing”4

The passion Koutroulis had for art also came through in his teaching and mentoring students. In a 2016 feature, published in the Metro Times, about a James [Jim] Crawford exhibition at Trinosophes, Crawford credits such educators as Aris Koutroulis, who taught painting at what's now the College for Creative Studies, and John Egner, who taught at Wayne State. “They were the mother hens of a lot of the stuff that was happening,” Crawford says. Add in all the working artists, a few edgy galleries, and you have a climate that can make things happen. "See what you have there is a community," Crawford says. "That doesn't happen very often. And that's why Detroit is so significant. That it did have a community that was vital enough to have a presence on a national scene. And it was because of a lot of different people, such as [DIA contemporary art curator] Sam Wagstaff, who gave it credibility. But it happened. There were enough people, and the community was tight enough."5

Egner and Koutroulis, were close friends until the end of Aris’ life in 2013. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, they both had studios in New York and Detroit, and would often make the flights back and forth together. Egner stated in an interview that he believed both Aris and he approached teaching in a similar way, in that they always looked for the potential within each student and that they acted as ‘talent scouts’.

Susanne Hilberry once said, “In fact the art was rougher here, slicker in New York. Something about the jerrybuilt quality of the art contributed to its intensity, and allows us at the same time to understand its tenderness.”6 These two artists were straddling the roughness of the art scene in Detroit with the slick, modernist art world of New York City in the ‘60s and ‘70s. This came through the work effortlessly, and the synthesis manifests itself in many different ways into the work.

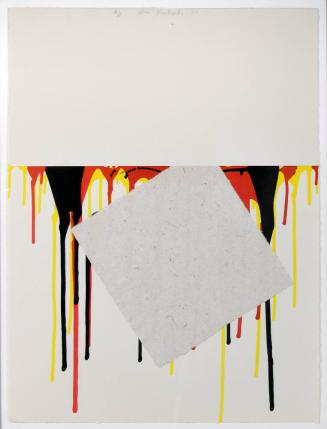

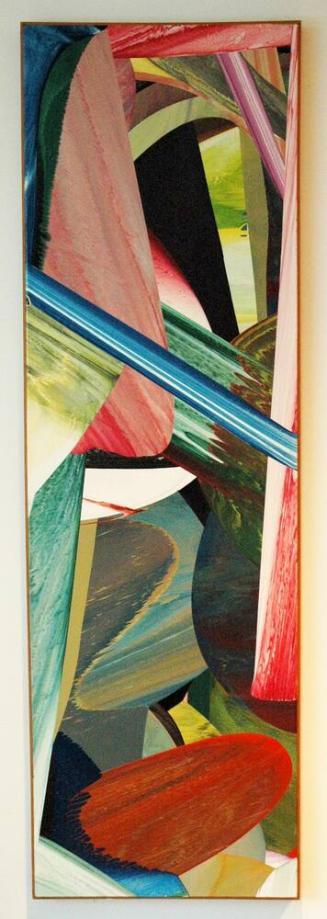

Egner’s After Blood and Never are from a series of large colorful paintings made over the course of nine years. They began when he was on sabbatical and worked solely in his New York studio. Egner explained that the paintings came out of a “desperation” and longing for access to his old methods of wood-working and painting that he had done in Detroit. Like Detroit’s motto ‘Resurget Cineribus’, written in the seal of Detroit in Latin, meaning ‘It will rise from the ashes’, Egner took his feelings of urgency and desperation and turned them in to artistic bravery. This body of work became a confrontation to his feelings of fear. The confident approach to mark making seen in these works came from his need to experience fearlessness in his art-making process.

After Blood expresses this fearlessness and simultaneously conveys both chaos and order. The background is expressive and fluid in contrast to the perfect geometry applied to the surface. It asserts tension between the calculated structure and the unpredictable organic movement.

After almost nine years of making large scale paintings, such as Never and After Blood, UFO #3 became a turning point for Egner. He started to create works on a smaller scale which inherently made them more accessible, and humble. Even though the pieces were smaller in scale, the boldness found in the larger works remain evident in UFO series.

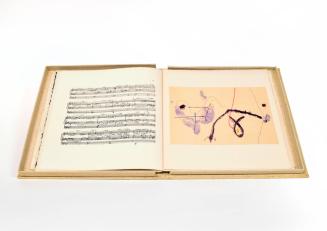

Merry Christmas Jim, and Untitled, are small scale Christmas cards created for James Pearson Duffy (also known as Jim), a legend in the Cass Corridor. He is remembered as an eccentric, generous, intelligent man with incredible influence on the art scene in Detroit during the days of the Cass Corridor that can still be felt today. Duffy was very passionate about the community, and supported Detroit artists in the Cass Corridor like no other. The people he supported were an extension of his life and he treated them like family members. He endowed Wayne State’s Art Department, which is named after him, and made many gifts to the University Art Collection and the Detroit Institute of Arts. “To Jim it was all good; it was the good that mattered. He loved making a difference, making grand supportive gestures, helping, being part of the process,” reminisced Egner. “For Duffy, though, the quest was a two-way street: discovering meaning in an artwork helped him discover a bit of each artist’s genius and at the same time allowed him to claim part of his humanity.”

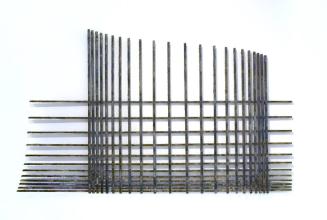

Doug’s Smoke, a lattice piece created with oil paint on wood, is both a structural and organic form just like many of Egner’s paintings. This piece is an example of his ability to push the boundaries of traditional painting. Although it is a construction made of wood, Doug’s Smoke is a paintings which collectively captures both physical and illusionistic space. This play between the organic and synthetic mirrors the corridor artists’ play between seeing objects as trash or treasure. The work is thought out, calculated, and inspired from everyday life in the Cass Corridor, as the name hints to Doug James, a student at Wayne State University.

Paris, Amsterdam stands out among Egner’s works, evoking the chilly feeling of winter’s first frost. Paris, Amsterdam is an emotional, introspective piece that was made in a hotel room in Amsterdam in 1973. The sculptural texture of the work is created with oil stick, pencil, and crayon on wood. The work is reminiscent of the style of the artist Frank Stella, famous for his use of minimalism and post-painterly abstraction, who Egner studied with during his time at Yale.

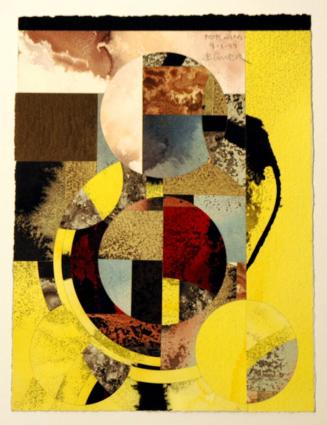

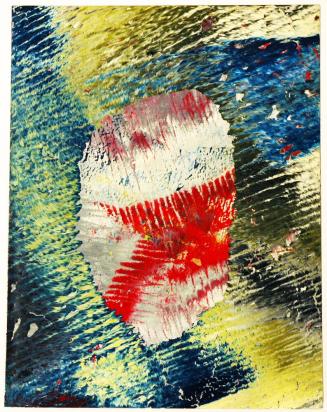

Koutroulis, another important mentor to students, brought New York art world exposure to Detroit. He channeled his life history and influences of working in Detroit into his work. Evidence lll, a color lithograph made in 1971, speaks about violence, and the work remains proof of a situation. The essence of the print is the aftermath of a crime scene, or explosion. Considering Koutroulis’ childhood, and the violence he witnessed during the war, his art became his own form of evidence to early life experiences. In addition to that, when one looks beyond the possible meaning of the piece to the technique, his transcendence of print media is revolutionary. Printmaking is a medium that is bound by process and tradition. Koutroulis runs from these parameters and pushes the very nature of a print. Detroit also exposed him to turbulence times. Evidence lll is abstract enough of speak of violence in both a general and nuanced ways.

Untitled, a large scale acrylic painting, with Koutroulis’ signature drips, reflects his influence of automatic writing. The practice of automatic writing, also known as psychography is the activity of writing without a conscious idea or thought in order to allow subconscious or spiritual influences to appear in the writings. From a far, the piece looks like a scroll and the drips appear to be a language of their own. The drips aligned in rows can be viewed as writing on a wall, literally and metaphorically.

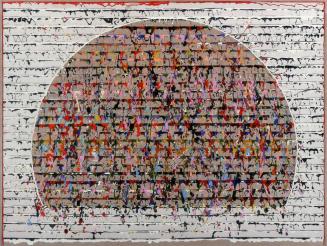

The painting Emergence, a large scale painting featuring a half-circle in the middle, is evocative of something both ancient and modern. The impression of automatic writing remains. In the words of Michael Florescu, “Crucial to an understanding of Koutroulis’ intent is to recognize that the finished works are perfectly organic: there is total absence of illusion.” 7

Ox-Bow V, the title derived from a residency in Saugatuck, Michigan, uses subtlety instead of brash lines to communicate the damage that is present when something is broken. Koutroulis uses the technique of cliché verre, a method that combines painting, drawing, and photography, to push the concept of what makes a print. Again, the work speaks of violence. An object that has been violently fractured, reflects Koutroulis’ own life experiences physically and psychologically.

The artists in the Cass Corridor took control back into their lives during a very chaotic time by using objects in their surroundings. Artists took one man’s trash, and made it their truth. Some believe that art is merely a luxury, which exists only for its beauty. At its core, art is a function of survival. Artists make work to process their place in the world around them and to communicate, while art viewers consume art to gain a greater understanding of the world around them and inside of them. The internal world of emotions, thoughts, and memories experienced and interpreted, mirrors the external and become a window to the human experience. Snowden stated in her Cass Corridor documentation project oral history8, “If you’re living hand to mouth in the Cass Corridor, you’re not going to be painting pretty pictures. The work is a reflection of your life. That was a big thing for me to observe. Your work is a reflection of who you are.”

The art of John Egner and Aris Koutroulis provides us with a glimpse into the world of Detroit during the 1960’s and ‘70s, when the city experienced devastating violence and everlasting changes. As a mirror, the artwork allows us to look at ourselves. After Blood and Never reminds us of times in our lives where we’ve made bold, brave decisions. Emergence reveals the sum of small, continual actions built into a reaction, relating to the larger context of our lives. The experiences of Egner and Koutroulis, and all of the artists from the Cass Corridor, have shaped the history of the arts at WSU and art in the city of Detroit.

Written by Emily Borden