Ellen Phelan: Survey of Works from the WSU Collection

After the decline of Detroit starting in the 1960s, the Cass Corridor located in the west side of Midtown near Wayne State University had an intense spike in artistic activity. Although these artists worked, attended art school, and lived side-by-side, they did not share a unified style. Instead, they found their own niches in which to flourish and "cross- fertilize" in collaborative spaces with one another.[1] Collectively, they worked in the rigid shadow of minimalism and all shared “anti-formalist” sentiments that led them to appreciate the exploration of materials and processes.[3] Even though these artists created radical spaces, physically and socially, female voices were not loudly represented. With notions like, “tough guys making tough art” defining such works, it can be clear how women struggled for representation. [1] Urban expressionism and "anti" formalism were forced interpretations of Detroit's Post-Modern style, by this group known as the Cass Corridor artists. This gritty industrial interpretation of contemporary art was not always understood or embraced outside of Detroit. [1] However, years later, a reevaluation of these artists is due.

Ellen Phelan is one of the women artists in the Cass Corridor movement whose career shows continued reflection and adaptation from her student years in Detroit to carving a path that was distinctly her own. Born in 1943, she spent her childhood in Detroit and graduated from Wayne State with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1969, and a Master of Fine Arts in 1971. She followed opportunity and moved to NYC in 1973, drastically changing her career to not be bound by the limits of a predominantly masculine art scene in Detroit. At odds with prevailing trends and known for her stubbornly honest work, Ellen Phelan has pushed the boundaries of contemporary painting for over 50 years, and advanced her career from that of a renowned Detroit artist into one of an artist with a global reputation and successful career. [3.5]

At Wayne, Ellen received formal academic training while also being exposed to innovative ways of using traditional art-making techniques, such as Cliche-verre, taught by renowned printmaker and painter Aris Koutroulis. However, Phelan like many of her classmates was surrounded by the physical decline of industrial Detroit, influencing their interests and use of found and repurposed objects to create artwork. Gestural abstraction to symbolic representation was a familiar trope between this generation of artists, usually with a visual dialogue between these two ends, spanning over decades. [3]

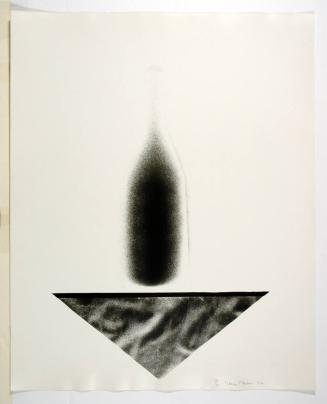

Phelan’s early works speak to her formal training and initial contemporary nature. Unlike the Cliche-verre studied, which replicated etched semi-photographic landscapes, Phelan, who was surrounded by formalist rules, was encouraged by modernist theory to examine and defy such rules. Untitled (From Ten Black and White Portfolio) combines representational and geometric shapes and soft and hard edges to create a more contemporary approach to the use of this traditional print-making technique.

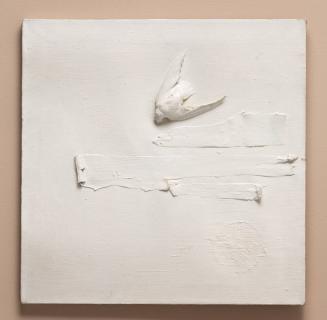

Like her contemporaries, Phelan uses found objects in her early work, Moon Bird. Encapsulated in the painting is the corpse of a bird. She admits she was confused and intimidated by color for a long time, choosing to highlight form and support over anything. [6] This early piece shows love for natural form, letting physical shadow substitute value.

In a time where the international dialogue surrounding painting was thought to be exhausted of anything new to say or show, many painters were trying to reinvigorate painting all together. Attempting to see something new, Phelan explored the relationship between painting and sculpture, taking canvases off stretchers to combat the frustration she felt by the constraints of two-dimension. Untitled (Shield) and Untitled are examples of this early frustration. Large, free hanging, cut canvas is painted on either side to show the plane of each fold. [3] Treating canvas like fabric and sculpture helped her emulate a feminist version of Robert Morris’s minimalist works which triggered empirical interest in process. [5] Cut and folded canvas evolved into “soft-form” sculptures of canvas wrapped around wood or other materials, functioning as shaped supports for paintings. [3]

United (Chair) and Untitled (Wrapped grid) demonstrates this relationship between painting and support. Strips of painted canvas are wrapped and used like collage and paint.

By 1972, she started a series that occupied her for three years, constructing plaster fan- like structures, some small and some to the size of her body. Fan, described as a “self supportive painting”, were free standing canvas, again, redefining 2D supports as they become 3D sculpture.

With the encouragement of other women artists like, Elizabeth Murray, Jennifer Bartlett, and Jackie Winsor, Ellen moved to New York in 1973. Shortly after her arrival, she met the sculptor Joel Shapiro and they were married five years later. By 1976, she began to explore abstractions that highlighted the relationship between color and form that adopt a three-dimensional format. These pieces combined two and three-dimensional methods while still paying homage to both landscape and figure. [3]

In the late 1970s, Ellen began painting on metal plates with gestural strokes. Working wet-to-wet she created interlocking units. As her artwork evolved, a deeper sense of imagery developed; aligning landscape and figure would be her task for the first half of the 80s.[3] Intending to be interchangeable parts, Four Part Cross are panels linking color and form.

Phelan soon returned to tonal paintings as starting points with more consideration of the use of color. She began spending summers in the Adirondacks and returned to making representational landscapes. After many years of focusing on the exploration of formal concepts and process-oriented artwork, she returned to making plein air gouache drawings. These drawings signaled her renewed interest in realism.

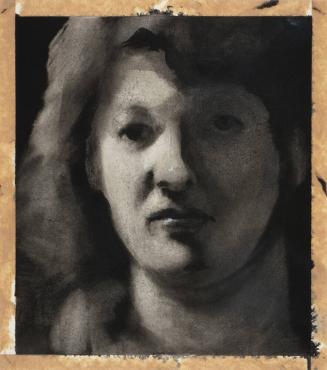

Her comfort working in black and white is evident in these paintings, reflective of her early drafting days at Wayne State under teachings of Robert Wilbert, which led her to think about light and then color. ‘Goldsmith’s Road, Loon Lake’, ‘Woods and Lake, Loon Lake’, ‘Fountain and Pool’ and ‘After Watteau: Assembly in a Park, Last Light’ were inspired by classical artists such as Corot, Turner and of course Watteau. [3] However, Phelan's paintings focus on new ways to represent the atmospheric tonalities, while removing figures altogether. And while she still continues to do portraits occasionally, they still have atmospheric and landscape qualities. [6]

As seen in Portrait of Nancy Mitchnick, These two portraits of her dear friend and fellow artist, show complete ease with use of gouache and its abilities to communicate atmosphere and range of value.

In 1985, Ellen's interest in still life resurfaced with a series of doll paintings on paper. Similar to plein air, the dolls began as black gouache paintngs, but much like still-life, she worked from observation. However, these works are far more than representation. These paintings skillfully transform inanimate objects and imbue them with deep intense psychological narratives in a theater of her own, challenging our imagination. “As opposed to the material projected by a child, the material I was projecting was adult, It really had to do with emotional relationships between men and women, mothers and daughters, gender definition and how it comes about, the female sense of self” Phelan says. [8]

“The dolls are a cross between my realistic landscapes and my still life’s- the origin of the gouache technique is in fact in the landscapes” Phelan says. [5] Both apparent in Applause and Baby and Pierre (Run Baby), The tension between subject and setting creates a sense of memorial. [8] Her proficiency in wet-to-wet and turpentine allows figures to appear stranded in time. By 1988, she began to look at her works on paper as starting points for paintings and reruns for landscapes. Based on her feelings and recollections, she creates stills of Norway, Mexico, Belize and Ireland, as well as landscapes from her summers on Long Island and Lake Champlain. This exploration of layering and light reveals expertise in representing the natural world. [3]

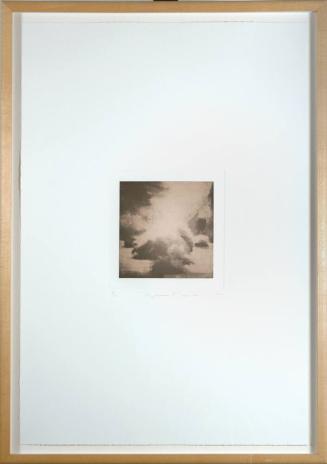

Throughout her career, she continues to emulate a sense of memory and collective longing, she would further this when she introduced photography. [5] A form she was denied from in her early years, she reclaims the use of family photos into “conceptual groupings” like a diary. [5] It became an intimate display of how she feels, even if it meant working against critical theory. Spring, First Drawing (From Garden: Amagansett portfolio) is an example of use of her photography and lithography skills to capture the tonality of things that are important to her.

After her mother passes in 1995, she unearthed so many family photos that were full of meaning to her. These photos represent the relationships in her immediate family that formed her ideas of development, companionship and adulthood. [5] Confronting

figurative painting yet again, she uses photos to paint portraits of her immediate family. Present in Joel on Foster Street, a combination of new use of photography and familiar use of gouache results in a portrait with qualities of landscapes and still life.

What follows these portraits are a combination of the qualities she found attractive in landscapes and still life paintings. Fueled by a love of her garden and showing personal narratives of domestic life, a series of florals were created. [7] She consistently captures mystery and intimacy that is reflected in her floral works and refines the traditional and restrictive nature of still life by incorporating romantic sentiments with her use of color and atmosphere as seen in Pink Rockwood (Champlain Roses). [7]

Ellen Phelan’s strength and tenacity are evident in her artwork, and its constant evolution, which in turn has had an impact on her career and her accomplishments. Ellen’s work is included in the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Fogg Museum at Harvard and so many more. She served as Chairperson of the Department of Visual Arts and Director of the Carpenter Center for the Arts at Harvard University. She has had exhibitions at museums and galleries around the work and has been represented by some of the most prestigious galleries in this country, including Barbara Toll, Paula Cooper and Susanne Hilberry Galleries. Her awards are numerous and include the New York Time Fellow, American Academy in Rome, American Academy of Arts and Letter and Wayne State University’s Arts Achievement Award. [3] Her sound academic training at Wayne State University and foundation as a leader in the Detroit Art Scene of the 1960 and 70s prepared Ellen for her future success and international career and show a coherent drive that Phelan has lived through rather than charted. Michele Gerber Klein would say, “Phelan is an intellectual.

Her art exists in reaction to, with and against her friends and other artists' works, critical theories and art history itself. There are no gaps, just tenses. And, more importantly with Ellen, different mediums, which is to say different languages” [5]

Bibliography

[1] Myers, Julia R. Subverting Modernism: Cass Corridor Revisited, 1966-1980. Eastern Michigan University Galleries, 2013.

[2] Jacob , Mary Jane. Kick out the Jams: Detroit's Cass Corridor 1963 - 1977. Museum of Contemporary Art, 1981.

[3] Armstrong , Richard. “Ellen Phelan To Date .” Ellen Phelan: From the Lives of Dolls, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, University Gallery, Amherst, MA, 1992, pp. 8–14.

[3.5] Goldwater, Marge. “Preface.” Ellen Phelan: From the Lives of Dolls, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, University Gallery, Amherst, MA, 1992, p. 7.

[4] “Gasser/Grunet Present First Major Survey of Ellen Phelan’s Works on Paper.” Edited by Jose Villarreal, Gasser/Grunert Present First Major Survey of Ellen Phelan's Works on Paper, 1 May 2012, https://artdaily.cc/news/55069/Gasser-Grunert-present-first-major-survey-of-Ellen-Phelan-s-works-on- paper.

[5] Klein, Michele Gerber. "Ellen Phelan." Bomb, 1 July 2004, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/ellen- phelan/. Accessed 25 April 2023.

[6] Loughery, John. “Landscape Painting in the Eighties: April Gornik, Ellen Phelan, and Joan Nelson,” Arts, May 1988, pp. 44-8, ill.

[7] Auchincloss, Rex. “Ellen Phelan Landscapes and Still Lifes: A Selection.” The Brooklyn Rail, 3 Mar. 2011, https://brooklynrail.org/2011/03/art/ellen-phelan-landscapes-and-still-lifes-a-selection.

[8] Henry, Gerrit. “Ellen Phelan: The Interpretaton of Dolls.” The Print Collector’s Newsletter, vol. 19, no. 2, 1988, pp. 51–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24553615. Accessed 3 May 2023.