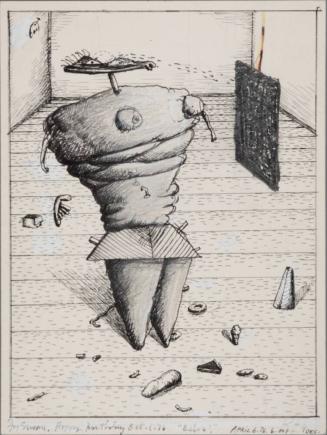

Airplane Drawing

Artist

Brenda Goodman

(American, born 1943)

Date1971

MediumPencil, oil paint on paper

DimensionsPaper Size: 40 × 26 in. (101.6 × 66 cm)

Frame Size: 44 1/4 × 30 in. (112.4 × 76.2 cm)

ClassificationsDrawing

Credit LineGift of Linda Dunne, 2008

Object numberUAC3060

DescriptionIn 1971, Brenda Goodman stepped back from her early, more abstract style of painting and exhibited a series of drawings of aerial battle scenes, featuring skies cluttered with waves of lumpy airplanes, drawn in an almost child-like style, as well as rockets, parachutes, and rubber-stamped numbers. In one, a picture featured in the DIA’s 1980 Kick Out the Jams exhibit, a squadron of aircraft is stacked up over a gas-masked man, who may be the target of the attack, or its leader; a small US flag is stuck in his scalp, as if his head was the battleground. This two-fisted subject matter was apparently of more interest to some of the male artists in the Cass Corridor scene than it was to Goodman herself. “The guys were all doing war and bullets,” she told the Detroit News in 2015, “and I wasn’t coming from that place.” Still, the drawings helped set her on the course that led to her later, more introspective and highly personal works.There’s nothing glamorous about the combat on display in WSU’s Airplane Drawing of 1971. The palette is drab and sickly, and the surface is dirty with smudges and smears of oil paint and graphite. Airplane enthusiasts will recognize amid the fray the distinctive silhouettes of two Second World War fighters, a Hawker Hurricane and an F4U Corsair; Goodman seems to have based some of her planes on reference photos, as well as her imagination. Authentic, too, is the sense of chaos: planes shoot past each other, one fighter falls from the sky trailing smoke, and bits of black and blood-red debris litter the sky. Near the top, a scarred and besmirched white wedge —an aircraft’s nose cone in the extreme foreground, perhaps, or even a grotesquely twisted face — stabs into the picture from the right. Goodman depicts war as an ugly and senseless undertaking. The drawing was donated to the Wayne State collection by Linda Dunne, a literature professor and former dean of the New School in New York.

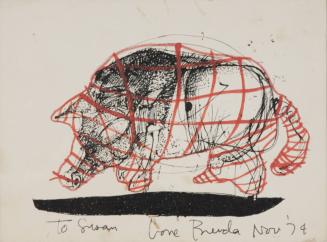

Another image of aerial warfare that Goodman made around the same time is so comical in comparison to the larger Airplane Drawing that it’s easy to imagine she sketched it up just to lighten the mood. Apparently done with colored felt tip pens, the battle in this smaller drawing is between striped snakes and long-eared rabbits, transformed into war machines with wings, jets, and machine guns. One serpent with a zig-zagging tongue rockets up to intercept a scribbly bunny-plane dropping carrots from its bomb bay. (The phallic appearance of the dangling carrots throughout the drawing may not be accidental.) Another airplane/rabbit hybrid, with whiskers, cotton tail, and the designation “R-1” stamped on its fuselage, seems to have been speared by a huge ballistic carrot — a victim of friendly fire? The drawing is addressed “For David,” meaning stockbroker David Zucca, an avid collector of Cass Corridor art, who donated the piece to WSU. “You talk about macho,” Zucca once told an interviewer, “you look at some early Brenda Goodman paintings, and those are painted like men — supposedly, what men think men paint like. Those paintings are tough.” It may be just a sketch, but this satirical version of war in the air at least drains some of the machismo from its subject matter.

_____

Native Detroiter Brenda Goodman was born in 1943. She studied at Wayne State, but she got her degree from the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies). There she received rigorous formal training, and honed her craft by copying both Old Master and Modern painters. Goodman turned the skills she acquired to exploring her own emotional and psychological state. Her work over the years has always included both abstract and narrative or autobiographical elements, existing somewhere between abstract expressionism and a kind of surrealism. She has taught and lectured around the country, and participated in numerous exhibitions. “My intent is to extend the parameters of my specific and personal issues to reveal and comment on basic universal emotions and conditions,” read her artist statement for a 2007 solo show at the Brooklyn Museum, which featured a series of starkly honest and revealing self-portraits of a woman then in her early 60s. “My work is about reality, not irony.”

Text by Sean Bieri

Collections