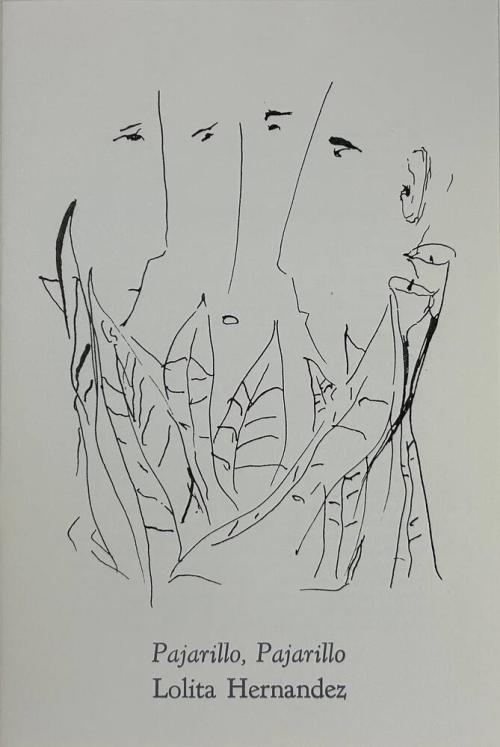

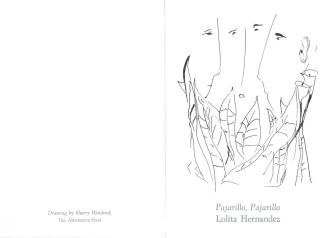

Pajarillo, Pajarillo

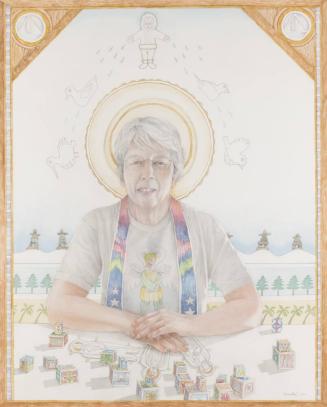

Artist

The Alternative Press

Artist

Lolita Hernandez

Datec. 1993

MediumLetterpress on paper

DimensionsPaper Size (folded): 9 × 6 in. (22.9 × 15.2 cm)

Paper Size (unfolded): 9 × 12 in. (22.9 × 30.5 cm)

ClassificationsPrint

Credit LineGift of Gary Eleinko, 2023

Object numberUAC7451.11

DescriptionLetterpress printed poem on paper by Lolita Hernandez, titled "Pajarillo, Pajarillo".Letterpress printed drawing by Sherry Hendrick.

Pajarillo, Pajarillo

(A movement from the fictional story This Is Our Song for Today)

If she put her ear up to the line after each engine passed

her station, she could hear a faint chirp. At first she thought

it was one of the many birds who became trapped inside and

flew frantically from high in the rafters looking for a way out,

but of course, they rarely found one. There was no way out up above

the lines. Only at the edges of the entire floor were there windows

but if a little bird could figure that out by flying low and straight

to the perimeters of the first floor, then it would have to worry

about passing through all the machinery in the cam department

or all of the lines and washers in the block department. Even if

it reached as far as the head line, things were so thick over there

who knows what could happen to a little bird. There was a wall

that extended for a good part of number one line that seperated

it from the rest of the department , making things cramped.

Everyone knew that little birds tended to become trapped in the

half-block area, hovering over it until they found a safe ledge

hopefully away from the line of piston trays that came from the

second floor to the piston-checking station. When a bird was no

longer seen everyone hoped that it had escaped through the

loading-dock area, but knew that the bird had become weak and

hungry and fell into the line and was carried away by the links

in the conveyor to the pit underneath. She figured that at change-

over, every year at the beginning of summer, when the cleaners

removed the sludge build-up under the line, they must see a

bushel or two of dead oily birds.

After spending two more months on her job, she began to

think that maybe the chirps were an echo from the real birds

flying above her. She would look up every time she heard a

chirp but could see no bird. She concluded that the chirps arose

from the spirits of the birds whose bodied dropped off the con-

veyor at her section because the sludge had lost its hold on them.

They were calling out to her. No one else heard chirps in the

line. She began to sing to them softly pajarillo, pajarillo, que

bonitos ojos tienes and a bird would answer back with a chirp.

Sometimes she would jiggle her timing chain over the line be-

cause she thought the jingling was a little like their muffled

chirping. Lastima que tenga dueno.

She worked her eight hours with her head bowed and lean-

ing into the line in order to not miss any chirps. For this reason

she had developed few friends in the factory. No one came to

visit where she worked because she gave the appearence

of being a loner or of being afraid of people. However, her co-

workers didn't consider her arrogant because her stooped, rounded

shoulders and her bowed head ( even when she was away from

the line walking to the bathroom or getting a cup of coffee from

the machine) made her look humble. Many of them realized

that she was just plain shy and also that she didn't speak much

English. Her smile, when she cocked her head to respond to a

greeting, was wide and toothy in order to convey her genuine

love of people.

She had learned the song from her mother who died many

years before in her home town of Agualeguas, Mexico. Her mother

had sung the same few words (nada mas) when washing the

dishes or espcially when making the tortillas. Pajarillo, parajillo.

Que bonitos ojos tienes. Lastima que tenga dueno. She thought

then that her mother should get tired of singing the same tune,

the same words over and over but it was a good thing because

now it is the only song of her mother's she can remember and

the words are firm in her heart and she had almost forgotten

about the song until the first time she heard a chirp in the line.

Published by The Alternative Press, Issue Number Nineteen.